The Upside to Learning Outside

How outdoor educational experiences provide new perspective for migrant students

By Samantha Ray | Photos by Cary Edmondson

As Jose Lomeli steps off the Greyhound bus, he feels the chill of the Lake Tahoe air hitting his face. It’s the winter of 1978 and Lomeli, a 20-year-old migrant student from Modesto Junior College, is surrounded by a group of soon-to-be teachers preparing for a five-day outdoor wilderness adventure with California Mini Corps.

He is immediately in survival mode. Along with a group of people he just met, he must survive in the mountains with only the equipment on his back. Lomeli quickly learns trust is key. He must rely on the strengths of the people around him to make it through this intimidating experience. As trust goes both ways, his peers had to rely on him to cook for the group.

Cooking was something his mother had always done. When Lomeli was a boy, she would wake up at 3 a.m. to prepare homemade tortillas and sopes for her husband and four sons along with packing each of them a day’s worth of food so they were ready by 5 a.m. to work in the fields.

Though Lomeli had learned from his mother, he felt the pressure of cooking outdoors for such a large number of people. But he learned to face his fears and discovered he enjoyed trying something new.

This was Lomeli’s first outdoor educational experience — and he was hooked.

During the week, he hiked, built shelters, navigated with a compass and rappelled off a 200-foot cliff. He connected immediately with Augie Perez, at the time a program facilitator for California Mini Corps and faculty at UC Berkeley and UC Davis. Perez taught Lomeli that outdoor education is impactful for its participants and is a teaching tool that can utilize nature to help people overcome challenges.

Fast forward 30 years, Lomeli, now a Fresno State professor, and Perez, UC professor emeritus, have been running outdoor educational experiences for migrant children almost every month.

Together they created Inter-Act, an organization that partners with county offices of education, migrant education and institutions to provide outdoor educational experiences to migrant and foster youth who would not otherwise have access to such summer camps.

“Myself and colleagues found that for migratory families, sending their children away for a week to summer camp was a foreign experience. We dealt with resistance. Migrant parents would often say, ‘Why should we send our children to outdoor camps? We live and work in the outdoors all day long. We want our children to wear ties and work in offices with air conditioning.’”

Educational outdoor approaches place an emphasis on the importance of human connection, building relationships, inspiration and personal motivation, Perez explains.

Fresno’s central location as the only major city in the United States within about an hour of three national parks — Yosemite, Kings Canyon and Sequoia — offers plenty of opportunities for outdoor recreation and education.

This past summer, the Department of Education’s Migrant Education program sent 60 San Joaquin Valley migrant children in grades 7 through 9 to participate in one of Inter-Act’s week-long outdoor education projects in Fish Camp. The children embraced the nature around them, eager to try zip lining, rappelling down trees and engaging in trust activities.

“I personally stepped out of my comfort zone various times, making my experience such a growing one, having much more confidence without letting fear control me,” says Cynthia, an Inter-Act participant. “When it came to activities, we needed spotters. I had trouble trusting, yet so willingly I depended on them. In life, the spotters are like family and programs at school that lend a hand.”

The children had to trust their peers in physical activities that require the help of others and push them to do something new or challenging. “The most important thing is that they make some connections,” Lomeli says. “They take the experiences they have, and they make connections to their own lives.”

Lomeli’s and Perez’s work in outdoor education has benefitted over 135,000 youth and adults in California — 55,000 through Inter-Act and about 80,000 with California Mini Corps — a majority of which are migrant children.

Together, they wrote a book titled “Outstanding Beyond the Fields,” a collection of short stories of migrant farmworkers who have benefitted from outdoor education. Lomeli uses the book to teach Fresno State students how storytelling increases retention. Because, as he says, reading a great story is hard to forget.

So, too, are transformative educational experiences.

— Samantha Ray is a communications specialist for the Kremen School of Education and Human Development at Fresno State

FRESNO IS THE ONLY MAJOR CITY IN THE UNITED STATES WITHIN ABOUT AN HOUR OF THREE NATIONAL PARKS – YOSEMITE, KINGS CANYON AND SEQUOIA

Spawning Outdoor Learning Opportunities

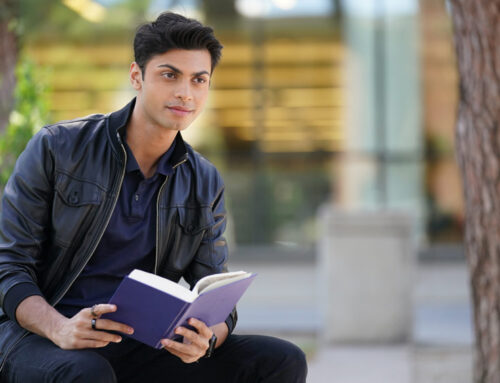

Antonio Valdez, a Fresno State alumnus and social worker for Kings Canyon Unified School District, started volunteering with Inter-Act in 2007 while a student at Fresno State. He now works to facilitate its outdoor activities.

Valdez grew up as a migrant farmworker. He remembers relocating to the Central Valley from Michoacán, Mexico at age 4. He lived with four other families in a van parked on the farm where he and his parents worked. He would wake up early in the morning and lay out paper for grapes to dry out and become raisins.

When Valdez was 20 years old, his mother passed away. That same year, he was introduced to outdoor education. “It was neat to be able to step away from everything and just be out in the scenery where everything disappears, it is just you and nature, and it was very therapeutic.”

As an undergrad and graduate student at Fresno State working with Inter-Act, Valdez, who is currently working toward his preliminary administrative services credential at Fresno State, learned tools that assisted him in his counseling career. Now working with high schoolers, Valdez says he builds similar outdoor experiences for children at Orange Cove High School.

“I love to do my individual counseling sessions outdoors. Sometimes being in a confined space can be awkward and sometimes students don’t want to open up,” Valdez says. “But as you are walking outside and breathing fresh air, it gives this sense of calm.”

Valdez remembers how hard it was for him to keep moving forward when his mother died, but Lomeli and Perez never gave up on him. That resonated with Valdez, and today he strives to be able to give back to others, just as Lomeli and Perez did for him.