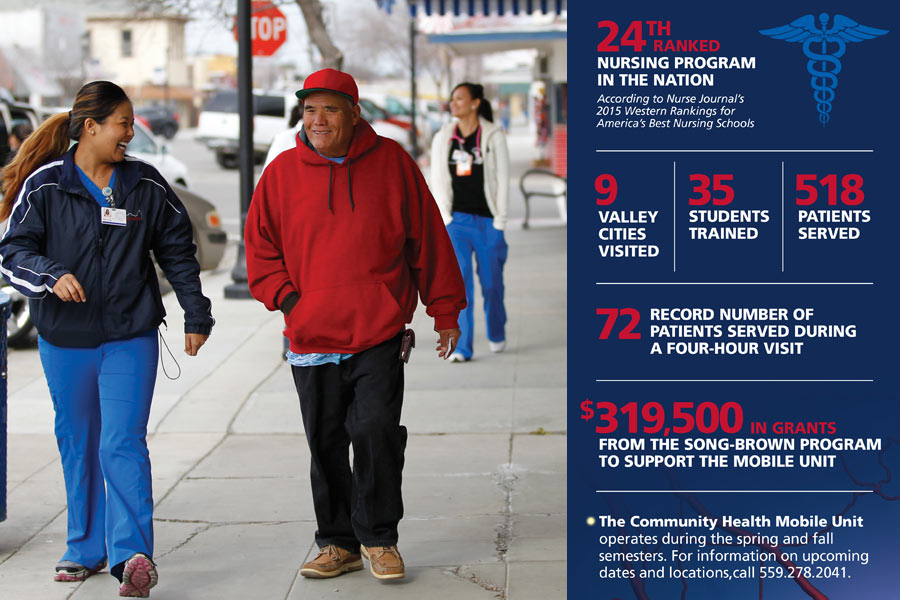

Nursing students provide free health screenings for local communities

Story by Eddie Hughes

Photos by Cary Edmondson

It was the middle of summer 2015 when Donald Ray Foster first passed out. It was just stress, he thought, or maybe a lack of sleep. So he didn’t visit a doctor to find out what was wrong. Foster had just moved back to Madera from Stockton, and the nearest clinic wouldn’t accept his medical insurance.

So he waited.

A few months passed without Foster seeking care until a November day when he and his wife noticed the Community Health Mobile Unit parked in front of the Hope House, a facility that provides behavioral health services in Madera County. Foster had just eaten lunch and started to feel faint again.

“My wife said, ‘Why don’t you go check it out?’” says the 43-year-old Foster.

“That’s when we found out I had diabetes.”

Foster learned of his medical issue while visiting Fresno State’s mobile health unit, a vehicle designed to provide free health care screenings for the underserved. The mobile unit is staffed by Fresno State faculty and students from the School of Nursing.

“Quite honestly, I would have probably ended up in a diabetic coma if they hadn’t brought it to my attention,” Foster says. “I would have let it go, and it would have gotten worse.”

MORE ACCESS TO CARE

Designed to help alleviate a shortage of primary care providers in the area while providing hands-on training for nursing students, the mobile unit departs the Fresno State campus every Tuesday morning and travels around Fresno and surrounding rural communities.

The mobile unit staff provides free education and screenings for blood pressure, blood sugar, cholesterol, heart and lung health and more. It’s designed to serve patients who cannot afford care or who don’t have convenient access because of transportation challenges. The unit also can help people who have trouble making timely doctors’ appointments.

“The doctors are so impacted, because there aren’t enough providers, that they can’t get everybody in for three or four months sometimes,” says Dr. Kathleen Rindahl, assistant professor and baccalaureate coordinator in Fresno State’s School of Nursing.

“So if you have high blood pressure and you can’t get in to see your doctor for three or four months, we help connect the dots, and if we find something urgent, we call the doctor and say, ‘Hey you need to see this person sooner.’”

Foster’s condition when he visited the mobile unit was the definition of urgent. His blood sugar level was so high it qualified as an emergency. The mobile unit staff sent Foster straight to the hospital, and he was treated and prescribed medication that alleviated his symptoms.

Other patients who have visited the mobile unit have benefitted simply from the education provided. During a February stop in Firebaugh, a patient was having trouble getting her glucose drips because of the cost, so the staff gave her resources on how to find them at a lower cost. The staff helped another patient find affordable eyeglasses. And many others receive education on lifestyle choices that can prevent problems like high blood pressure and high cholesterol.

The mobile unit typically serves 20 to 25 patients during each four-hour stop.

Students and faculty send flyers to local businesses, churches and fire departments prior to each visit, and they often walk the streets to encourage people to get check-ups.

Lori Harshman, a nursing graduate student with years of experience as a director of nursing at a long-term care facility in Auberry, says community outreach is the key to health education.

“It’s right here. It’s here being in the community,” Harshman says. “I think it’s walking up and down the streets. I think it’s all the outreach. If I can touch you, I can teach you.”

This project, the first of its kind at Fresno State, has touched and taught hundreds.

PHILANTHROPY DRIVES MOBILE UNIT PROJECT

Rindahl previously worked on the mobile unit when she was part of the migrant health program at the Fresno County Office of Education. When that program dissolved and Rindahl accepted a position at Fresno State, she knew the mobile unit was sitting unused in a parking lot.

Rindahl worked out a deal to use the mobile unit, and along with Dr. Cyndi Guerra, an assistant professor in Fresno State’s School of Nursing, acquired grants to fund the project for the next three years. The funding, Guerra says, allows the mobile unit to be stocked with supplies and pays for the fuel, driver and insurance for travel throughout the Valley.

“This is a nonprofit,” Guerra says. “We’re not here to make any money. We’re just here to provide a free service for those in need who don’t have access to health care.”

Fresno State’s College of Health and Human Services is working on a permanent funding model to keep the service alive and continue to address the shortage of Valley health care.

“Providing access to patients and families who can’t get preventative care could help improve the overall health of the Valley, which is not well known for being the healthiest place in the world,” says Sara Jennings, who has 10 years of nursing experience and is in her first year of the family nurse practitioner master’s program at Fresno State.

Learning by serving is part of the culture at Fresno State, where students, faculty and staff have volunteered more than 1 million hours per year of community service for five straight years. That giving nature is modeled in the School of Nursing as much as anywhere on campus.

“It’s important that we offer a service like this,” Guerra says. “As nurses and nurse practitioners, our whole goal in life is to be of service to our patients and to our community.

“It’s rewarding, and it’s something that, no matter how long you’ve been a nurse, you should always give back to your community in whatever way you can.”

Foster, the Madera patient who was diagnosed with diabetes, says he felt like he went back 70 years in time when staff from the mobile unit stopped by the Home Depot where he works to make sure he was on the mend weeks after his visit.

“It made me feel special. It made me feel that they cared about me,” Foster says. “They came and saw me at work to make sure I was doing OK. You don’t find that anywhere. I didn’t feel like just another patient, I felt like a person.”

And now he feels like a healthy person again — and he says he owes it to the Community Mobile Health Unit that happened to be in the right place at his time of need.

“Things don’t happen just by chance,” Foster says. “It’s for a reason in my book that they were there, and I was there at the same time. It’s not a coincidence. It was meant to be.”

— Eddie Hughes is the senior editor/writer for FresnoState Magazine.

IMPROVING OUTCOMES FOR MOTHERS, BABIES IN FRESNO COUNTY

By Melissa Tav

Fresno County, where more than 1,500 babies are born prematurely every year, was chosen as one of six sites participating in University of California, San Francisco’s $100-million, 10-year Global Preterm Birth Initiative.

These rates are among the highest in California and surpass some underdeveloped countries.

Jointly funded by the Marc and Lynn Benioff Foundation in partnership with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the initiative will study the epidemic of premature birth, which is the leading cause of death for newborns and the second leading cause of death for children under five years of age.

To address the epidemic locally, the Fresno County Preterm Birth Collective Impact Initiative was initiated to focus on improving outcomes for healthy babies and mothers in Fresno County. The Central California Center for Health and Human Services at Fresno State was selected to lead the effort.

As the backbone organization, Fresno State will help drive all major aspects of this initiative to connect organizations across Fresno County and amplify existing partnerships to gather data on the biological, behavioral and social factors that contribute to premature births.

Alameda County and San Francisco were the two other U.S. locations selected. International sites in the effort are Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda.

“We firmly believe that by working together effectively, we can address social and health system disparities across the county,” says Dr. Larry Rand, director of perinatal services at the UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital San Francisco Fetal Treatment Center and the initiative’s principal investigator and co-director. “By doing so, we can demonstrate to the rest of the state and nation how to turn the curve on this stubborn and tragic epidemic.”

— Melissa Tav is a communication specialist for the College of Health and Human Services at Fresno State.