Echoes of Change

A glimpse at Bulldog cultural activism across the years

By Esra Hashem (’13, ’16, ’21)

On the fourth floor of the Fresno State library, tucked away in the Special Collections Research Center, lies a box with the label “Campus Unrest.” It documents the years leading up to the first Vintage Days at Fresno State in 1975.

“Unrest” is a common word to describe the significant cultural, social and political turmoil at that time. The 1960s were characterized by anti-war protests and the Civil Rights Movement, and Fresno State students and faculty joined college campuses around the world in taking part in widespread political and social activism.

“A lot of modern day activism was born at institutions of higher learning,” says Varselles Cummings, director of the Cross Cultural and Gender Center at Fresno State. “If we think about the Civil Rights Movement, for example, much of that movement and push was from college students. Activism

is bred here.”

At Fresno State, students protested in the thousands against the Vietnam War, which ended one week before the start of the inaugural Vintage Days. Also in the 1960s and 1970s, they activated along with the United Farm Workers movement to advocate for the rights of Central Valley farm laborers. Historical newspaper clippings showcase the controversy that ensued when students attended a rally in support of a Black Panthers spokesperson. Students and faculty also protested about personnel issues and for programs for ethnic minorities.

What did the campus look like then? Different than it does today. Of the 14,846 students enrolled in fall 1971, 80% were white. Today, Fresno State is a designated Hispanic-Serving Institution and Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander Serving Institution, with a population of nearly 24,000 students, 15.8% of whom are white.

Activist voices

Manuel Olgin receives a certificate at the Chicano/Latino Commencement Celebration in 1978. He founded the celebration along with fellow graduate student Tony Garduque.

As the years progressed, student demographics shifted and diversified. Manuel Olgin recalls arriving at Fresno State in spring 1971. He was part of the growing Chicano movement on campus.

Olgin says the 1970s were a time of adjustment for society — for families to adjust to their children becoming first-generation college students, for high school teachers to encourage Chicanos to further their education, for college faculty to accept a more diverse student body, and for the launch of new programs and organizations.

“What our community needed here is pride in ourselves,” he says. “It’s not always easy, but if you have something that reflects and celebrates where you came from, who you are and where you’re going, that’s a Fresno State success model.”

In an effort to increase representation on campus, Olgin and fellow graduate student Tony Garduque launched the Chicano/Latino Commencement Celebration in 1977 as a part of their master’s theses. Today, the tradition brings thousands to campus annually.

“I’m astounded by our growth,” Olgin says. He remained involved on campus as an employee for years, and is still involved as a founding member and president of the Chicano Alumni Club, which also launched in 1977. What he hopes for Fresno State is continued representation of Chicanos among administration and faculty.

“I think there is vast room for improvement. You can’t ever say we’re done; we have to keep improving,” he says. “But I’m proud of Fresno State, and I always will be. I’m a Bulldog for life.”

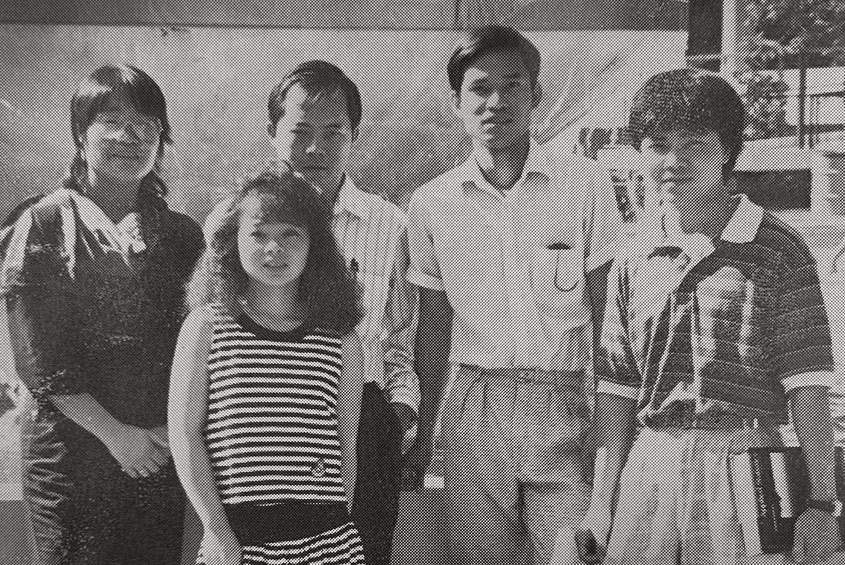

The late 1970s and 1980s saw an influx of Southeast Asian immigrants to the Valley. Dr. Katsuyo Howard, who arrived at Fresno State in 1972 from Japan, knew what it was like to be a foreigner in an American university. She advocated for the creation of Southeast Asian Student Services to help better serve students of these backgrounds.

Dr. Katsuyo Howard poses with students in a photo from the Southeast Asian Student Newsletter in 1989.

“If I didn’t have my background, I wouldn’t have been able to advocate for different approaches to teaching and counseling,” she says. “I used my learned knowledge to advocate for change. I wasn’t a refugee like many of these students were, but being a foreigner is applicable and helped me connect to them. And I immersed myself as much as I could — I even visited refugee camps, so I could better learn.”

Today, there are over 2,700 Asian students enrolled at Fresno State. The Valley has one of the largest Hmong populations in the country. The university’s Hmong minor was the first of its kind on the West Coast, and, recently, the university library entered a partnership to host a digital repository of historical Hmong stories.

“Systemwide change did not occur right away, but minorities became more involved as students, staff and faculty, and the representation began a slow change,” Howard says.

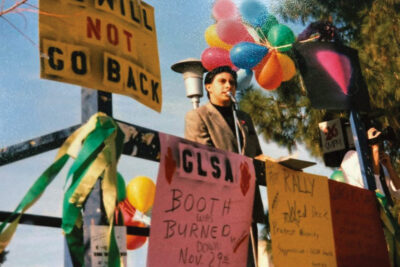

In the late 1980s, 14 students formed the Gay Lesbian Student Alliance (now called United Student Pride). They established a booth on campus, which was burned down by vandals shortly thereafter. A few years later, in 1991, Fresno hosted its first Pride parade, which lasted 10 minutes before ending in a brawl with the Ku Klux Klan. Dr. Peter Robertson, who was a student at the time and one of the founding members of the club, recalls the events.

As a student in 1987, Dr. Peter Robertson is quoted in the Fresno State Collegian telling onlookers: “The GLSA is not asking for your acceptance. We are demanding our civil rights. This is the United States of America. We demand our freedom. We demand our justice. We are entitled to our pursuit of happiness.”

“It was an interesting time to be out and proud on campus. We had a lot of support from our allies, but also a lot of pushback,” says Robertson, who is now the director of alumni connections at Fresno State. “While it was traumatic, we would not be where we are today if we had not done that then.”

Some of the recent progress Robertson is proud of includes witnessing the Pride flag being raised in June 2021 — now a yearly tradition — and the annual Rainbow Graduation Celebration, which was established in 2014.

“Looking back, I am so grateful for my lived experiences because it’s made me the person I am today,” Robertson says. “I would not be so passionate about helping students if my life at Fresno State as a student had been easy.”

Centering diverse programming

Throughout the years, Fresno State has developed programs and services to advance its commitment to equity. In 1990, the Women’s Resource Center was established as a designated space for women and women’s issues. The late Dr. Francine Oputa, who was known for her extensive work in social justice, was its founding director.

“The establishment of these programs and centers were a response to what was happening nationally and globally, as well as here in Fresno,” says Dr. Rashanda Booker, university diversity officer.

Since 1993, there were formal efforts to establish a cross-cultural center. A hate crime against Malcolm Boyd, a Black student, by the Ku Klux Klan in 1997 intensified this need, and serious conversations about what the center would look like occurred. Those conversations led to the development of what is now called the Cross Cultural and Gender Center. It was led by Oputa, and is now overseen by Cummings.

The center’s vision is to create and maintain a campus of respect, inclusion and equal opportunity. It has programs and services for African American, Native American, Asian and Pacific Islander, Latino/a and LGBTQ+ populations. The center is housed under the Division of Equity and Engagement, led by the university’s first-ever diversity officer, Booker.

“We understand the trajectory that higher education has gone through in the last century. It was very monolithic, created for and by a certain, particular type of individuals, which were white, cisgender, Christian men,” Booker says. “And so over the last century or so, access has begun to allow different people from different types of backgrounds and beliefs to start coming in. The university diversity officer position is really a response to that. It’s about helping individuals feel like they belong in a place that was historically not for them, but today, it is for them.”

The ongoing work

Fresno is nestled in one of the most culturally diverse regions in the nation, and Fresno State history consists of countless significant cultural moments — ones that have challenged, enriched and transformed us.

Booker acknowledges that sometimes higher education is slow to respond to the demands of activists — but that their activism is never in vain.

“Higher education is a system that was created to maintain itself and continue to reproduce the same thing over and over. And that’s why change is slow,” she says. “That is across the globe, not just Fresno State. But change has happened and is still happening.”

A look at Fresno State’s history showcases its rich diversity. The Collegian’s first ethnic supplements, for example, were launched 55 years ago. The annual affinity celebrations for cultural groups during graduation began in 1977 with the first Chicano/Latino Commencement, founded by Olgin and Garduque. The Peace Garden (comprised of monuments of social justice leaders) was established in the 1990s, and is still growing today. And most recently, for the 10th consecutive year, Fresno State was awarded the INSIGHT into Diversity Higher Education in Excellence in Diversity (HEED) Award.

But the work is ongoing, and fostering an inclusive and equitable campus requires critical thought and community collaboration. Cummings himself, a Black man, recalls growing up in Fresno being unsure if Fresno State was the right place for him. His own experience highlights the need to continue fostering an inclusive environment.

“My hope for the future of Fresno State is that we continue to grow and move the needle so that students who are currently enrolled here see this as a place that belongs to them, that they can be proud to say that they attended,” Cummings says. “And that new students and future students see this as a real contender, not just because of academic accolades or rankings, but because they feel like this is the place that will support and grow them holistically and embrace all of the identities and perspectives that they bring to campus.”

– Esra Hashem is the director of strategic communications for University Marketing and Communications at Fresno State.

Top photo: Cesar Chavez sits with Fresno State students during a Nov. 3, 1972 rally against Proposition 22, an initiative that would have guaranteed the right of workers to organize but placed heavy restrictions on the right to strike, boycott and picket.